Historic Quarrying

The question of how much damage was caused by the historic quarrying and stone removal at the America’s Stonehenge is a significant one. The damage from stone removal and the subsequent restoration efforts by William Goodwin in the 1940’s to repair the damage from stone removal as well as damage from natural processes has caused the academic and archaeological communities to deeply question the archaeological integrity of the site. The often quoted estimate that 20% to 60% of the site’s stone was removed has reinforced the perception that the site was irreparability damaged and therefore not researchable. An inquiry into the basis of this estimate found it was purely speculative and not based upon any scientific review. To address this problem, the authors conducted a detailed analysis of the physical archaeological evidence of stone quarrying and stone removal activity to assess the extent of the damage and losses. The analysis determined that (1) the damaged sections of the stone structures can be clearly identified, and (2) the damage was minimal.

Historical Evidence

David Goudsward has conducted detailed research into the Pattee family who lived on Mystery Hill. Goudsward states that Jonathan Pattee died in 1849 and his son Seth Pattee acquired the property. Shortly thereafter records of stone removal from the site occur in the historical record [actually only one reference]. Goudsward argues that Seth Pattee, Jonathan’s son, was responsible for much of the damage to the site caused by stone removal. Seth circumvented the tax on quarried stone by removing pre-quarried stone from the site. [The “quarry tax” is a myth, there was no such tax]. In 1863, Seth lost the property to his son George in an inheritance dispute. George sold the property in the same year to Nathaniel Paul, a lumberman, who stripped the hill of its trees (Goudsward 2003, 60). In Goudsward 2006 book, “Ancient Stone Sites of New England” he largely backs off his original statements about the quarrying. He acknowledges that there were only two wagon loads of stone removed from the hill top by Seth Pattee. He references Salem town records for this information. Another researcher, Joanne Lambert states that Jonathan Pattee allowed John Leverett to remove stone from the site between 1845 and 1848. She further states that Nathaniel Paul who bought the property from George Pattee allowed further quarrying or stone removal from the site between 1863 and 1891 (Lambert 1996, 29). Lambert never cites her sources for this information.

In addition, to the above published books there are oral stories from local residents of wagon loads of stone being carted away from the hill (Hanion 1993). Again this no independent confirmation of any of these stories.

Given the lack of reliability of the published accounts of quarrying activity, one must turn to the archaeological evidence to properly assess the question of how much damage was done by stone removal activities on the site.

|

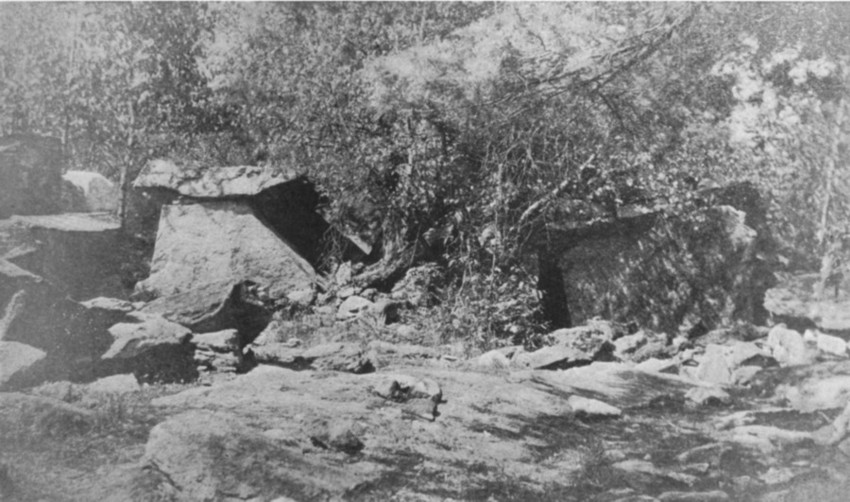

Circa 1900 Photograph of the Oracle chamber Alcove showing all the roof slabs and right side walls stones intact.

Quarry Drill Holes

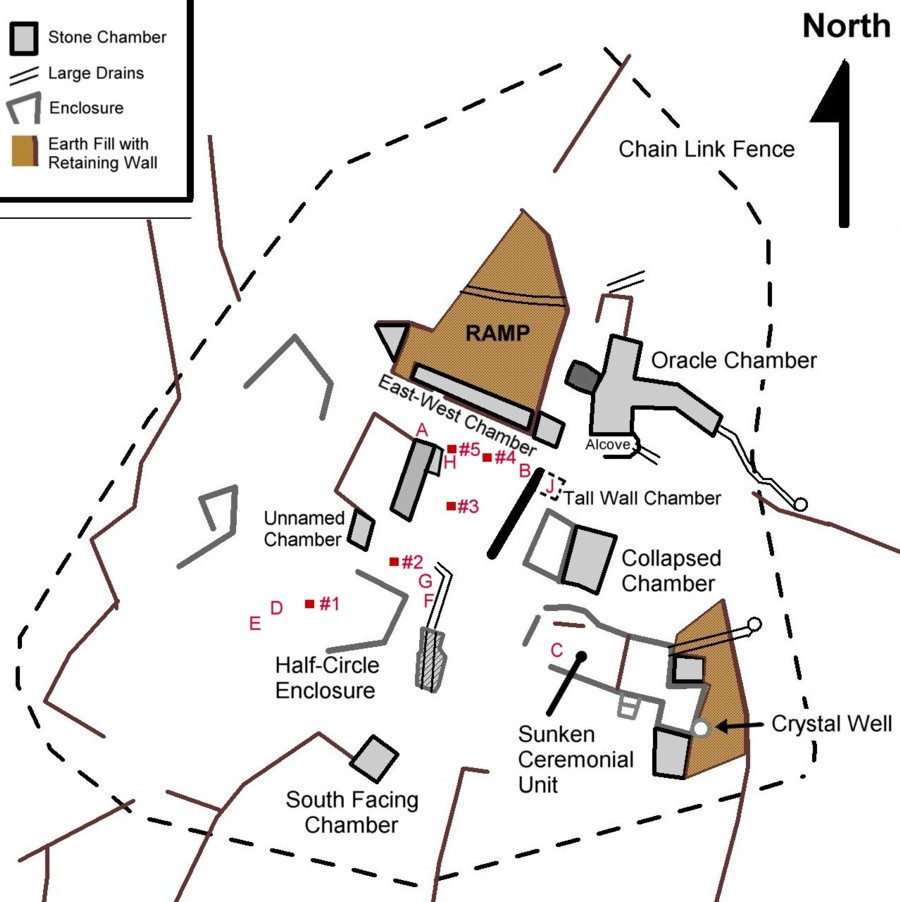

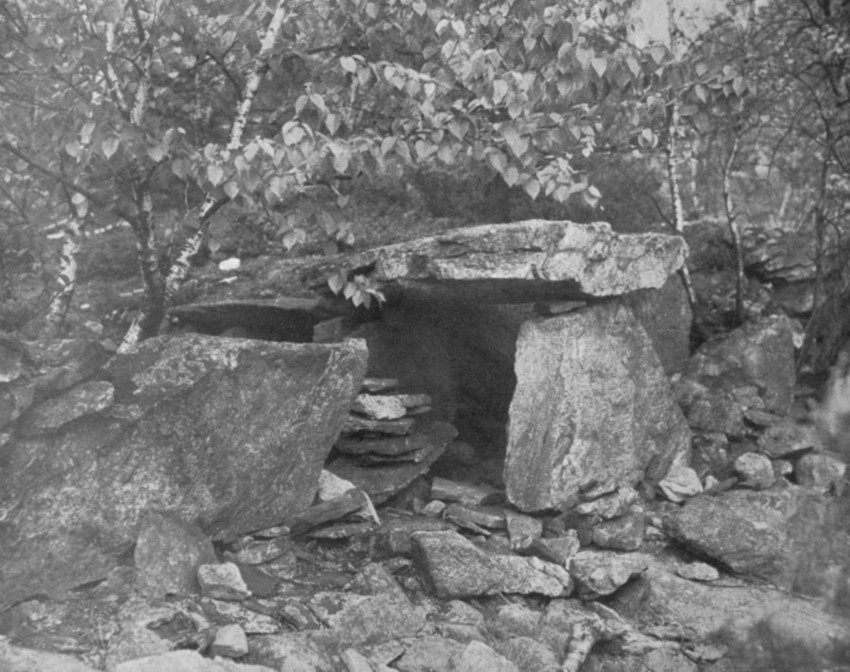

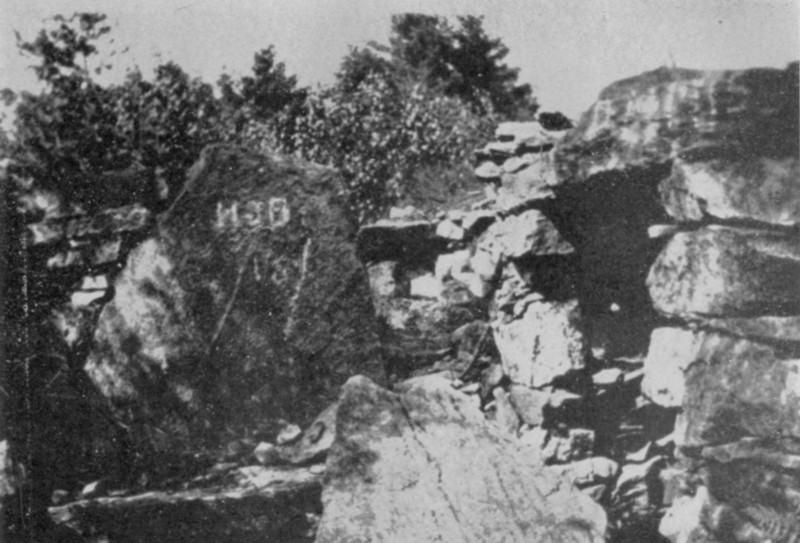

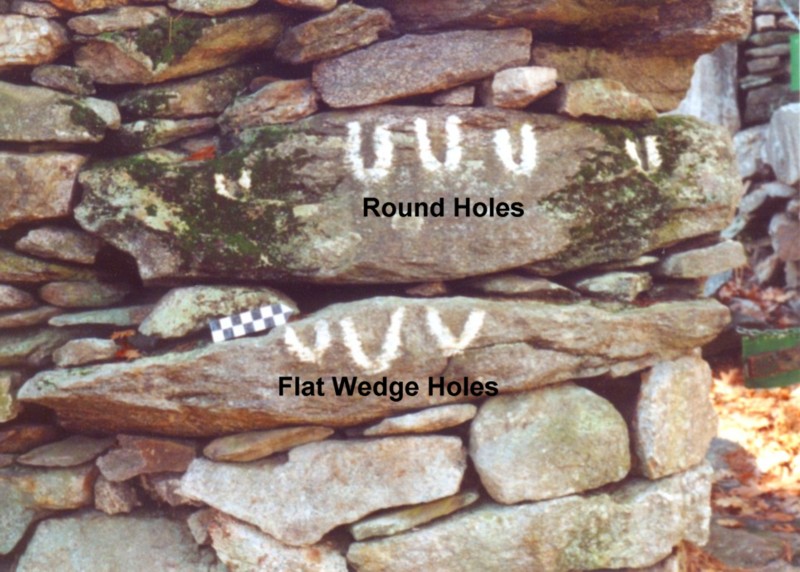

Two types of 19th century drilled holes were found on site: (I) Elongated flat trapezoid shaped hole known as a flat wedge hole, which were used with the flat wedge method (dates to 1800-1870) and (II) round drill holes which appear as half round drill marks after the rock is split into two pieces. The round holes were used with the plug & feather method which dates to 1820 or later. Twenty-two round drill holes were documented at the site. In addition a square hole created by using four round drill holes, and a 90 degree hole created by using two round drill holes were found. Four different diameter round holes were documented ½ inch, 5/8 inch, 1 inch, and 1½ inch. Three half round drill marks are found on the northeast corner (“H”) of the roof slab of the Tilted Roof Chamber (a/k/a “Mensal Stone”). The corner of this roof slab was removed using the plug and feather method of stone splitting. Three half round drill marks spaced about 7 inches apart were found on a slab on the north end (east side) of the Tall Wall (“J” on map). This slab was the top roof stone of the Tall Wall Chamber. The protruded section of the slab was split and removed using the plug and feather method. Below this slab was a second roof slab which has three trapezoid shaped flat wedge quarry holes. This slab was split off using the flat wedge method and removed. These are the only examples of flat wedge holes on the site.

The remainder of the round holes were whole and not split in half. They are located in the following places on the site:

* Letters denote locations on the map

A. Three holes drilled in the bedrock a few inches northwest of the corner of the Tilted Roof Chamber (“Mensal Stone”).

B. A single drill hole in the bedrock on the west side (near the north end) of the Tall Wall.

C. Two round holes and a square hole created by chiseling out four round holes in a large stone slab in the Sunken Courtyard.

D. A single round drill hole was found in a stone slab west of the Half-Circle Enclosure (“Pulpit”). The hole currently has a sign post inserted into it.

E. A 90 degree hole drilled in a stone slab just west of the Half-Circle Enclosure (“Pulpit”). It was created by drilling round holes from two different angles until they intersected with each other.

F. Row of eight round drill holes spaced 4 inches apart along the edge of drain D14. They are located east of the Half-Circle Enclosure (“Puplit”).

G. Row of six round drill holes spaced ½ inch apart. The intervening stone between the holes was partially removed (broach channeling technique).

Round holes A through D were for eye bolts and other hardware to attach guy wires for the hoisting apparatus. Hole E was designed to allow a rope or cable to loop through it and likewise functioned as a guywire anchor point. The purpose of the row of holes at F & G is not completely clear. Row F may have been the beginnings of a sixth socket hole (discussed in next section). Row G could either represent an attempt to quarry the bedrock or were for eye bolts or other hardware.

|

Two slabs once forming the roof of the Tall Wall Chamber were split off and removed.

|

The corner of the Tilted Roof chamber (“Mensal Stone”) was split off.

Drill holes Location “C” Drill Hole location “D”

Drill holes location “G” Overall Photo Showing Locations “F” and “G”

Hoisting Apparatus Post Holes Sockets

Five square sockets were cut into the bedrock. They are three sided square sockets with a level flat bottom chiseled out of the bedrock. Some examples have evidence of round holes in the corners suggesting the perimeter of the socket was cut first using a broach channeling technique. A possible unfinished sixth example (“G”) illustrates the technique. A line of closely spaced round holes were drilled and the intervening rock between the holes was broken away with a chisel. Once the perimeter was well defined the rock in the center of socket could be chipped out with a hammer and chisel. The five finished sockets measure 9”x9”x9”x3”, 8”x4”x1½”, 8”x10”x10”x1”, 7”x16”x4”, and 10”x?x12”x2½”. These sockets were used to hold a vertical post for a hoisting apparatus for lifting stones.

|

Typical Example of Socket for the Vertical Mast of the Hoisting Crane

Socket #1 is located west of the Half-Circle Enclosure (“Pulpit”). Socket #2 is located just north of the Half-Circle enclosure. It was carved partially into bedrock and partially into a stone slab. The slab has shifted position and the socket is no longer square. Socket #3 is in the middle of the plaza between the Titled Roof Chamber (“Mensal Stone”) and the Tall Wall. Sockets #4 and #5 are both located 12 feet south of the East-West Chamber. Socket #5 is currently 30 inches away from the split off end of the Tilted Roof Chamber slab. The corner of the roof stone was removed to accommodate the hoisting apparatus.

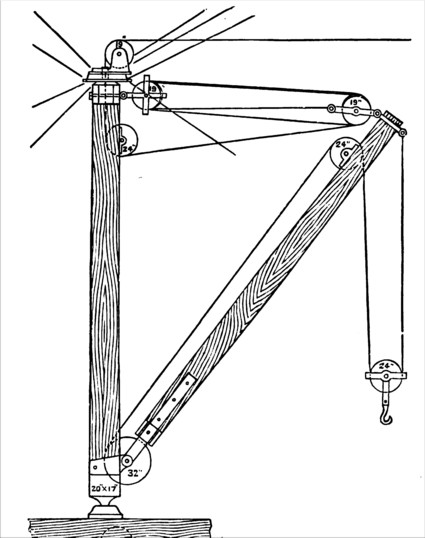

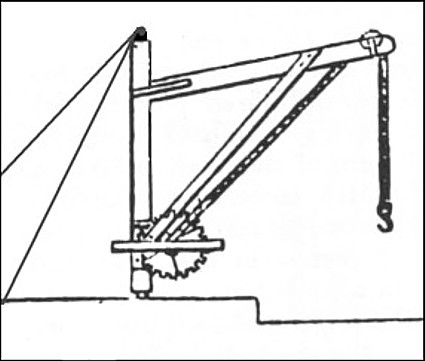

What type of hoisting apparatus was used? There are two possibilities. The first possibility was a quarry derrick. The second possibility was a jib crane. A derrick has a vertical mast pole either round or octagonal in shape mounted on a pivot mechanism which allowed it to swing around in a circle. Attached to the mast pole was a boom that had a hinge mechanism that allowed it to be raised or lowered. Pulleys were needed to raise and lower the boom, and at least two additional pulleys were needed for the hoist line used to handle the stone load. A mechanical wench was needed to raise and lower the load. Derricks were an expensive crane requiring a lot of specialized parts. It is highly unlikely such a small stone removal operation could justify five derricks. In contrast the jib crane was simpler and could be built primarily with locally available parts. It consisted of a square vertical post mounted on a pivot mechanism which allowed it to rotate. A square post was attached horizontally to the post and supported by a brace creating a swing arm. The lift line could be handled by a mechanical wench and pulley, or a block and tackle attached to the swing arm. The simplicity of the design and readily available lumber and hardware from local sources makes this the most logical candidate for the hoisting apparatus used at the site.

(Left) A typical 19th Century Quarry Derrick (Right) A Typical 19th Century Jib Crane with Wench Mechanism

There is a logical arrangement to the jib crane sockets. Cranes #4 and #5 could swing their load to #3. In turn #3 could swing its load to #2 and #2 could swing its load to #1. The location of #1 could be reached by a wagon or cart with little or no obstructions. Photographs from 1930’s and 1940’s show the main complex of the site covered with loose stone debris. Some of this debris was most likely from the stone removal operations but the need to swing removed stones from crane to crane suggests much of the debris predates the removal operation involving the cranes. Sections of the main complex which were not subject to stone removal (like around the large grooved stone) had an extensive layer of stone debris according to photographs from the 1930’s. This adds support to this argument.

Damaged Structures

Both roof slabs of the Tall Wall Chamber were split and the protruding halves removed. The other halves of both slabs are still embedded in the Tall Wall. The presence of flat wedge quarry marks on one of the slabs indicates this occurred between 1820s and the 1870’s when this method was abandoned and no longer used. The East-West Chamber sustained the greatest amount of damage. Two pre-restoration photographs taken in the 1930’s show the center section of the chamber heavily damaged. The wall slab forming the middle of the chamber is clearly missing. The roof slab for the middle section is visible in the photos and was never removed. Whether this section of the chamber had one or two additional roof stones which were removed is unclear. Goodwin’s crew subsequently filled the middle section with solid stone fill. It is agreed upon by most researchers that the upper sections of both the Tall Wall and the wall above the Tilted Roof Chamber (“Mensal Stone”) were restored by Goodwin’s crew. Whether they were damaged by stone removal or an earthquake is not clear.

Pre-Restoration Photograph of East-West Chamber from the 1930s. (Photograph probably by Malcolm Pearson)

Pre-Restoration Photograph of East-West Chamber from the 1930s. (Photograph probably by Malcolm Pearson)

Post Restoration photograph of East-West Chamber

Discussion

A review of the pre-restoration photographs and the physical evidence has established that one wall slab from the East-West Chamber and two half roof slabs from the Tall Wall Chamber were removed. There is no compelling evidence that any other slabs or bars are missing from the site. The extensive amount of stone debris visible in pre-restoration photographs of the main complex raises doubts as to how much loose stone debris was carted off.

In the three cases in which stone was split, the workmanship was amateurish and displays a lack of experience with stone quarrying. This is certainly consistent with the historical evidence suggesting individuals were trying to enrich themselves by exploiting the site’s stone resources. The five jib crane sockets indicate a lot of preparation work. The position of the sockets suggests an attempt to remove the East-West Chamber slabs. However, only a single wall slab and possibly one or two roof slabs were removed from the East-West Chamber and possibly some stone cobbles or rubble from above the Tilted Roof Chamber (“Mensal Stone”) and from the Tall Wall. Both were within reach of the cranes.

For anyone familiar with stone masonry work or stone quarrying, the reason for the failure of the various attempts to quarry and remove stone from the site is self-evident. The quality of the stone was poor. The stone structures were constructed from surface bedrock. The surface granite at the site is crisscrossed with quartz veins, has pockets of poorly mixed minerals, and is naturally fractured. In short, the surface bedrock was not structurally sound and has a very low weight bearing capacity. It is not the quality of stone one wants to use for a building foundation. Based upon the poor quality of the stone, it can be reasonably surmised that the individuals trying to sell the stone were unable to find a buyer.

Stone Slabs in Main Complex (Prior to Stone Removal)

* This list consists of stone slabs within the main complex at risk for stone removal. The Oracle Chamber and South Facing Chamber were not included. The persons involved in the stone removal activities made no effort to get at the roof slabs of either chamber (with the exception of the alcove) and therefore they are excluded.

4 Exterior wall slabs in East-West Chamber

1 Interior wall slab in East-West Chamber (between the large and small room)

3 Roof slabs for East-West Chamber (possibly 1 additional roof slab unconfirmed)

2 Roof slabs in Tall Wall

1 Roof slab of the Tilted Roof Chamber (“Mensal Stone”)

1 Fallen standing stone slab just west of Tilted Roof Chamber (“Mensal Stone”)

3 Slabs on top of Square Chamber (“Sundeck”)

1 Roof slab of Square chamber (“Sundeck”)

1 Grooved Stone

2 Standing stones near the Grooved Stone

2 “Sawtooth edged” slabs reported by Goodwin but currently missing

2 Roof slab in alcove of Oracle Chamber (one removed post Goodwin due to safety concerns)

1 Large roof slab in Collapsed Chamber (& unknown number of smaller slabs & large, thick slabs in east wall of chamber remain as well.)

1 Wall slab of Abandoned Chamber

1 Large & 2 small roof slabs in Triangular Chamber (“V-Hut”)

1 Roof slab in Unnamed Chamber

4 Roof slabs in Sunken Courtyard Chambers

1 Slab in Sunken Courtyard used as anchor point for guywire supports

1 Standing stone in Low Walled Enclosure

2 Standing stones in Upper Processional Way near main complex

--------

35 Slabs Total (does not include stone bars)

Confirmed Losses

1 Wall slab in East-West Chamber

2 Slabs in Tall Wall split and ½ of each removed

1 Roof slab in alcove of Oracle Chamber & two wall bars

Conclusion

Based upon the evidence, it is concluded that the quarrying and stone removal operations were small, limited, and ceased operations shortly after commencing. Of the thirty-five stone slabs at risk for stone removal within the main complex and adjacent areas, only four slabs were completely or partially removed. The top sections of both the Tilted Roof Chamber (“Mensal Stone”) and the Tall Wall may have also been damaged due to the stone removal activities. The damage to site was minimal and the extent of the damage can be established from pre-restoration photographs and other evidence. There is sufficient surviving archaeological and photographic evidence to determine in some detail the design and construction of the few structures damaged by stone removal operations. The argument that the site’s archaeological integrity has been compromised by the stone removal is without merit. The site is still very researchable.

The references for all the articles on this website are consolidated on the Bibliography page.